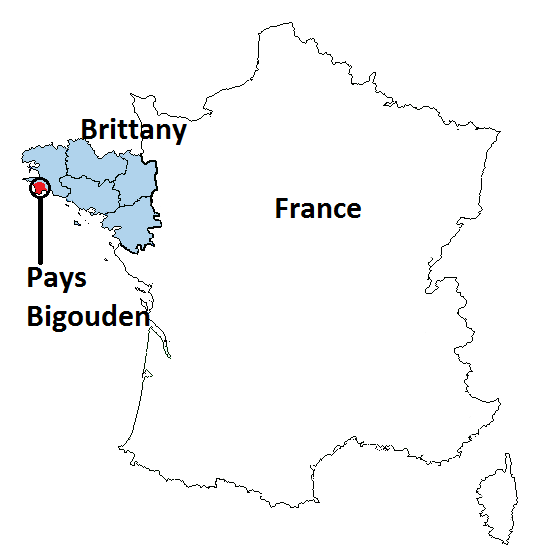

The French have always considered their northwestern province of Brittany to be a bit strange, and the Bretons have happily returned the compliment. The Bretons, Celtic to the core, are proud of their cultural and (until recently) linguistic differences from the rest of France. There is, however, one corner of Brittany that even the Bretons find weird, and that is the area that they call “Bigouden country” — le pays bigouden in French, or in Breton, ar vro vigoudenn.

With 55,000 inhabitants spread over 378 square kilometers, the pays bigouden is similar to a rural American county. The name Bigouden, which translates roughly as “land of the points”, refers to the pointed headdress once worn by the women; but it could equally well have referred to the area’s geography. Situated at the far southwestern corner of the Armorican peninsula, south and west of the departmental capital Quimper, the Bigouden coastline alternates between broad, sweeping beaches and wild rocky points that thrust out into a not always welcoming ocean. It’s a wind-whipped landscape that has always been populated by rugged fishermen living in rugged coastal villages, and by hardscrabble farmers inland — two groups that have had little to do with each other over the centuries, and even less to do with the outside world.

Viewed from the cosmopolitan city of Quimper, ten kilometers away, the Bigoudens appeared alien and uncivilized. “The Bigoudens are deeply ugly, and have nothing in common with the Greek type,” wrote Count Mahé de la Bourdonnais in 1892. “[They] still possess, in the decadence of their world, the gentle errors and the blind felicity of our most primitive inhabitants.” The count then added: “They strike me as being of Tibetan origin.” His contemporary, Dr René Le Feunteun, thought the Bigoudens were Kalmouk or Tartar. He had this to say about them in his doctoral dissertation: “[Here] lives a strange population, who are Breton in language only. [...] They all have ears of an enormous size, obvious sign of degenerescence. [...] Not very intelligent, of a sordid lack of cleanliness, they live in intimate promiscuity with their animals.”

Other amateur ethnologists came up with equally colorful theories as to Bigouden origins: Mongols, Phoenicians, Turks, Spaniards, Carthaginians, even Polynesians and, perhaps inevitably, one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. Many thought the Bigoudens were the sole survivors of a race that inhabited the Armorican peninsula before the Celts. DNA research has shown that the Bigoudens do indeed form a recognizeable genetic group, but that they are overwhelmingly Celtic, having more in common with Wales and Ireland than with some of the more Francified areas of Brittany itself.

Right in the middle of this proud, isolated vro vigoudenn was the village of Lanvern, absorbed today into the community of Plonéour-Lanvern. In the seventeenth century, Lanvern was nothing more than a group of farms clustered around two chapels. Like most of Europe at the time, the farms were owned by local nobility, and were worked by peasants who thereby earned the right to live on the land and to keep a quantity of the produce that, at least in good times, would feed their families. One of those families was called Le Minor.

Lanvern today. Barely visible to the right of the farm is the ruined tower of St Philibert’s chapel.

Actually they were called Ar Minor, because most of the calling would have been done in Breton and not in French, which was not widely spoken in Lanvern until the twentieth century. Nonetheless in the civil registries and parish records, which were mostly in French, the surname appears as Le Minor. The Breton word minor means “orphan”, which probably describes the sad state of the family’s male ancestor at the time that permanent surnames became the fashion, likely somewhere in the fifteenth century or so.

Unfortunately the written records don’t go back that far, for one dramatic reason: They were destroyed in 1675 during a wild uprising against the feudal and clerical authorities. The uprising, known to history as the Revolt of the Red Bonnets, was triggered by King Louis XIV’s effort to introduce a stamp tax, but in fact its roots lie in Brittany’s particularism.

*

Brittany has been formally part of France since the late fifteenth century when its last independent ruler, the teenage Duchess Anne, married two French kings. One condition of the marriage contracts, and of the subsequent Treaty of Union, was that Paris would have to respect Breton autonomy on questions of taxation; that is the reason, for example, that French highways impose no tolls within the five departments of Anne’s former realm. But French administration is irredeemably centralist, so that the Treaty of Union has been observed more in the breach than in obedience. For over five hundred years, therefore, Breton culture has displayed a simmering resentment towards French authority that has occasionally broken out into open revolt. This is what happened in 1675.

Louis XIV was at war with Holland and needed money. It must have rankled him that Brittany was not paying its fair share; so when in 1674 he imposed a stamp tax on all official documents including vital records, then made those vital records mandatory for all of his subjects no matter how poor, he made sure that the new impositions were announced in Brittany as a fait accompli, not requiring approval of the Breton provincial parliament. Riots broke out in Rennes, Nantes, and other Breton cities (and also in Bordeaux, proving that Brittany was not the only province that resented royal high-handedness). Urban riots had happened before, and the authorities were prepared for them, but they were less ready for what happened in the Breton countryside.

Beginning in the late spring of 1675, the rural protests that had flared sporadically became more organized. Peasant militias formed and attacked the castles, monasteries and manors of the feudal and clerical aristocracy. Archives of the hated official documents were burned, and the clerks and lawyers who maintained them were publicly humiliated or killed. Such incidents occurred all across Brittany, but were especially violent in the Bigouden region where the depredations of the nobility had been particularly harsh. In the first modern use of the color red to symbolize revolution, the insurgents took to wearing red bonnets, which gave their revolt both an emblem and a name.

In July, in the Bigouden chapel of Notre Dame de Tréminou, a group of Red Bonnets drew up a list of political demands and had them read out at Sunday masses across the region. The good Count Mahé de la Bourdonnais, down whose aquiline Greek-type nose he would sneer at the uncivilized Bigoudens two centuries later, might have been surprised to read the articulate and forward-thinking manifesto that his backward simpletons had produced. The demands included an end to the practice of landlords skimming off a percentage of every harvest; representation of the peasantry in the Breton parliament; abolition of or strict limitations on several forms of fees and taxation, including the stamp tax and the droit de banalité (see below); and even the right of women to choose their own husbands, a practice that Louis XIV had specifically outlawed a few years earlier.

The demands of the Red Bonnets would return a century later during the French Revolution, but in 1675 their time was not yet ripe. In August the Duc de Chaulnes led an army of six thousand men against the insurgents, and within three months the uprising was extinguished. There followed a year of trials, hangings and imprisonments. Six Bigouden chapels whose bells the Red Bonnets had rung to mobilize their members had their bell-towers decapitated. For the peasantry, deeply religious despite their anticlericalism, this was the most humiliating of all the French king’s reprisals.

Parish church of Lambour, Pont-l’Abbé, one of the six decapitated chapels.

(Photo: Jules Robuchon, circa 1890)

*

One observer of, and quite likely a participant in, these dramatic events was a peasant named Yves Le Minor, whose marriage to Jeanne Le Glorennec on 12 February 1684/85 and death on 19 December 1704 “at age 65” are recorded in the Plonéour parish registry; thus we can date his probable year of birth at 1639. Yves is the earliest Le Minor in the post-Red Bonnet records. His son Henri Le Minor (1692-1766) was followed by another Henri (1743-1807), Jean-Joseph (1785-1839), and then René Louis Le Minor (1824-1894). These men were all farm workers in Lanvern, moving from one estate to another, but all within an hour’s walk; they lived as their ancestors had lived, and probably in the same circumscribed area, since time immemorial. But René Louis Le Minor broke the pattern.

René lived in a troubled time. The French Revolution had disrupted and divided Brittany just as it had every other region of France and Europe; Napoléon’s military adventures had ended at Waterloo just nine years before René’s birth, leaving a legacy of large-scale military conscription that subsequent rulers were all too happy to use. Educated sons of the nobility, particularly, were subject to seven years of army service, but could escape that responsibility by paying someone else to do it for them. René Louis Le Minor sold his services in this way twice, serving in the army from 1844 to 1858, a period that included Napoléon III’s adventures in Italy and the bloody Crimean War. When he returned from his second seven-year tour at age 34, he had saved enough money to break out of the peasant life.

Return from Crimea (Auguste Goy, circa 1856)

Musée de Kerazan, Loctudy, France

On 19 May 1860, René married Céline Augustine Guichavoi (1838-1924) in Pont-l’Abbé, seven kilometers from Lanvern. Pont-l’Abbé was an actual town, the only one in the Bigouden region, with over four thousand inhabitants. Family stories describe Céline as “a woman as wise as she was beautiful”. Her father Mathieu Guichavoi was a shoemaker in Pont-l’Abbé, and her mother Olive Marrec ran a stall on the Plas ar Marc’hallac’h (Horsemarket Square). From her parents Céline inherited a business sense that would serve her new husband’s accumulated savings well; and from her mother she learned that commerce was not the private reserve of the men.

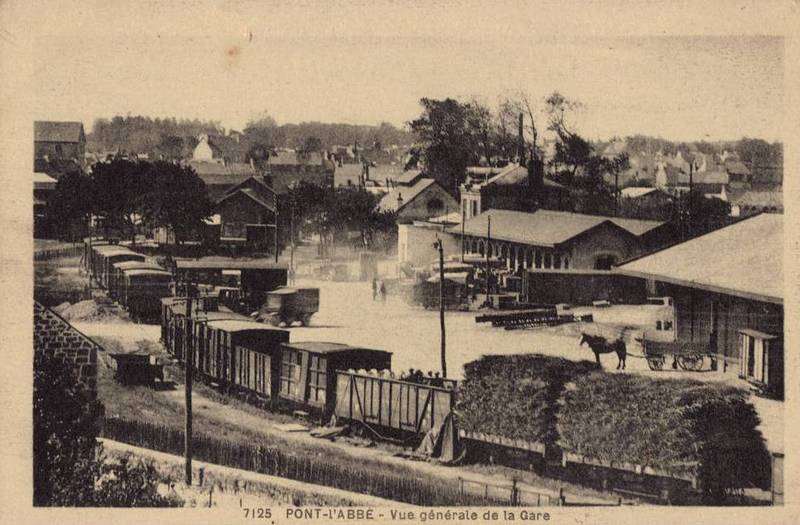

The young couple set up a small restaurant and guest house on the rue Meur, in the Penn-ar-Pont district of Pont-l’Abbé, which Céline ran while René brought produce from the Lanvern farms to feed the growing town. In the 1870s the town politicians began to agitate for the railroad to be extended from the departmental capital of Quimper to Pont-l’Abbé; this was approved and the line opened in 1884. Céline and René moved their restaurant to the rue de la Gare, in order to be near the site of the future railway station. From here they did a booming business feeding and housing the workers. René’s food wholesaling business also benefited greatly from the railway, since the Bigouden farmers he served now had access to the Quimper market as well as the one in Pont-l’Abbé.

René and Céline had three children: René Michel (1861-1924), Louise Célestine (1863-1868), and Céline Marie (1866-1945). The younger Céline never married; she inherited the family restaurant, which she ran for decades, acquiring the affectionate and quirkily noble-sounding nickname of “Céline de la Gare” — a sort of baroness of the train station.

The younger René quickly showed himself to be a sharp businessman, extending his father’s produce business into an emporium dealing in goods of all kinds. He also longed for the trappings of social status. On 19 April 1890 he married Jeanne Riou (1870-1951), daughter of Jacques Riou, scion of an ancient Bigouden family who owned huge amounts of land in the area.

René Michel Le Minor, Jeanne Riou, and their 11 children in 1918.

(Photo: André Kervennic)

The Riou family was not of noble blood, but rather represented a special class of Bigouden society that might best be described as a rural bourgeoisie. Since at least as far back as the mid-eighteenth century, this small landholding family had been lending money at interest, a practice frowned upon by the church but welcomed by all other segments of Bigouden society. They were, effectively, the local bankers, and they used their earnings to extend their land holdings. By the early twentieth century these holdings stretched in a continuous chain from the Ile Chevalier to the town of Combrit eight kilometers away.

René Michel Le Minor and Jeanne Riou had eleven children, all of whom survived to adulthood, and each of whom received land and a substantial house. The Le Minor family had risen, in the space of two generations, from Lanvern dirt farmers to one of the most prominent of Bigouden names. Then, on 30 June 1909, René Michel Le Minor scored his most impressive coup by acquiring the oldest and most emotionally-charged symbol of Bigouden nobility: the baron’s mills.

*

In the early years of the Breton immigration to the Armorican peninsula, and probably at least from the sixth century AD, there was an abbey near the present-day location of the fishing town of Loctudy. The monks of the abbey built a bridge over the unnamed tidal river leading to their domain, and the town that grew up around the bridge was called, in Breton, Pont-an-Abad, meaning Abbot’s Bridge; in Latin it was Pons Abbatis. Today, in French, it is still called Pont-l’Abbé, and is the “capital” of the Bigouden region. The bridge, much narrower than the present one, had a bend in the middle from which two jetties projected, one upriver and the other in the seaward direction. The jetties were used to load and unload boats; the seaward one also supported a calvary, long gone today, from which the bridge took the name of Pont Christ.

Over the centuries the importance of the local nobility increased at the expense of the abbey, which was finally abandoned after a series of Viking coastal raids. By the eleventh century the lord who controlled the strategic bridge (known as the Seigneur du Pont, and later as the Baron du Pont) not only dominated the Bigouden region, but was able to project his power as far as the Breton royal courts in Rennes and Nantes. The barons constructed a castle overlooking the bridge, and dammed the river. Two tidal mills were constructed on the bridge: a large one belonging to the baron himself, and a smaller one for the chaplain of the baron’s private chapel. Ownership of the smaller mill later passed to the priory of Notre Dame des Carmes, a hundred meters down the river from the castle, which the baron built in 1383.

The bridge and castle of Pont-l’Abbé in about 1400. North is up.

The two buildings on the bridge are the two mills.

(Drawing by Emile Ducrest de Villeneuve, 1893)

In order to protect the monopoly of his mills, the baron forbade any flour mills that he did not authorize to operate within his domains. (This practice, known as the droit de banalité, was common in feudal France, and often applied to communal ovens as well as to mills.) Naturally this generated resentment in the peasant population, who were forced to pay a milling fee for their grain, in addition to the other onerous exactions of the feudal system. When the Red Bonnet Revolt of 1675 reached the Bigouden region, one of the insurrectionists’ demands was the abolition of the droit de banalité. Both the Baron du Pont and the clergy at Notre Dame des Carmes were compelled to flee the area. Only the arrival in force of troops from Paris restored order.

During the French Revolution the last of the Barons du Pont was evicted, and in 1836 the castle became (and still is) the city hall of Pont-l’Abbé. The mills on the bridge passed into private hands. In 1848 they were purchased by a brilliant civil engineer with the marvelously florid name of Hyacinthe Le Bleis. Le Bleis, the son of a poor cobbler, showed an aptitude from an early age for large-scale construction projects; it is not clear how such a poor and presumably illiterate boy could have learned such skills. But he did learn them. Houses that he built in Pont-l’Abbé are still prized today. In the nearby coastal town of Lesconil he constructed an immense Dutch-style polder, and he had a similar project in mind for the river downstream from Pont-l’Abbé for which he never succeeded in obtaining permission. Through his massive works he became perhaps the wealthiest commoner in the Bigouden region.

Le Bleis removed the Pont Christ, replacing it with the broader and more solid structure that we see today. The new bridge supported not only the roadway, the dam and the two mills (now greatly expanded), but also a five-story warehouse from which Le Bleis ran his engineering and milling businesses. Between the two mills he constructed a small shipyard. By the late 1850s Le Bleis was running the second-largest milling operation in France, thus dominating Bigouden grain production. In other words, Le Bleis succeeded in maintaining the barons’ milling monopoly through non-feudal means.

Inevitably, such large-scale industry brought with it large-scale social issues. The town of Pont-l’Abbé, always an island of political activism in the generally placid Bigouden sea, became caught up in the social turmoil of the early Third Republic. Inspired by new socialist ideas and the push for secular schools, the turn of the twentieth century witnessed a number of strikes and confrontations between progressive and traditional forces. On 19 November 1906 the mills on the bridge, symbols of social and economic oppression for eight hundred years, were heavily damaged by a fire of uncertain origin. The top two stories of Le Bleis’ warehouse, then in the hands of a family named Laurent, had to be demolished. The mills themselves lay in ruins for nearly three years until they were purchased by René Michel Le Minor in 1909.

*

Even though the Bigoudens like to proclaim their differences from the rest of Brittany, and the Bretons theirs from the rest of France, the three cultures share a jealousy of success and an often well-founded suspicion that personal wealth comes more often from treachery and/or the luck of inheritance than from the meritocracy of hard work. René Michel Le Minor must have known that he was buying into centuries of resentment when he acquired the baron’s mills and the bridge from which his home town took its name.

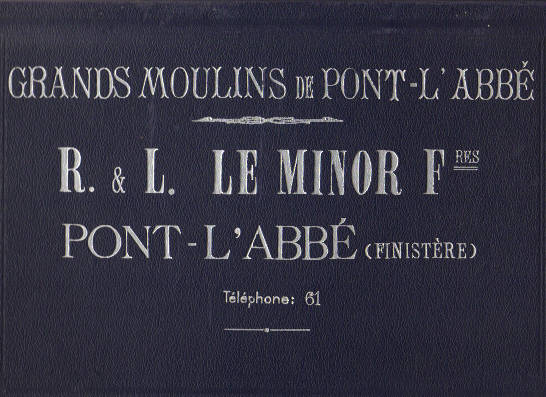

Within three years René and his two eldest sons, René (1891-1990) and Louis (1892-1957), had the mills up and running again; they became the centerpiece of the family’s mercantile business, which was now known as the Etablissements Le Minor, and whose prestigious new address was Les Grands Moulins, Pont-l’Abbé. René (the son), Louis and their families continued to run the mills for half a century, until they succumbed to the general large-scale industrialization of French agriculture in the 1950s. Louis, however, had returned from World War I nearly blind. Louis was a naval accountant aboard the French battleship Diderot, which participated in the Otranto blockade and served as a support ship for the ill-fated Dardanelles expedition of 1915. Louis, locked in a dimly-lit office for months at a time, emerged from the war with weak eyesight. During the 1920s he underwent two rounds of experimental eye surgery, but these did not help; he was therefore not in a good position to run a business. Luckily, he had a wife who could.

The French battleship Diderot.

Louis Le Minor married Marie-Anne Cornic (1901-1984) on 19 April 1920. Louis’ choice of bride was both surprising and a sign of the times, for Marie-Anne Cornic was not a Bigouden. She was born in the commune of Plonevez-Porzay, a few kilometers outside the area where the Bigouden headdress was worn. That would have made her an alien in the nineteenth century, but by 1920 the long isolation of the Bigoudens was melting away.

Marie-Anne’s parents  ran a general store in Plonevez-Porzay, specializing in clothing. Her father, Corentin Cornic (1870-1952), was an intellectual of impressive credentials for the time. He was among the first in his town to take his baccalauréat degree, even though he had to travel to Rennes for the exam. He spoke five languages fluently, including English; he traveled to Canada three times, where fanciful family stories recount that he purchased one-tenth of the province of Saskatchewan. In fact he took out settler’s claims on two 160-acre parcels in the township of Biggar, Saskatchewan. In the claims, he lied that his family was living on the land, when in fact they were all back in Plonevez-Porzay. His Garrec in-laws wound up moving to Saskatchewan and farming, and thus owning, the two claims, resulting in some ill feeling within the family.

ran a general store in Plonevez-Porzay, specializing in clothing. Her father, Corentin Cornic (1870-1952), was an intellectual of impressive credentials for the time. He was among the first in his town to take his baccalauréat degree, even though he had to travel to Rennes for the exam. He spoke five languages fluently, including English; he traveled to Canada three times, where fanciful family stories recount that he purchased one-tenth of the province of Saskatchewan. In fact he took out settler’s claims on two 160-acre parcels in the township of Biggar, Saskatchewan. In the claims, he lied that his family was living on the land, when in fact they were all back in Plonevez-Porzay. His Garrec in-laws wound up moving to Saskatchewan and farming, and thus owning, the two claims, resulting in some ill feeling within the family.

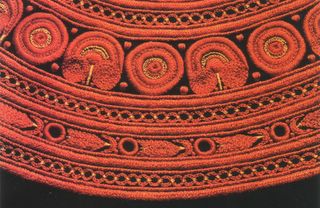

Corentin Cornic, therefore, was not around much. It was Corentin’s wife, Anna Garrec (1872-1926), who ran the family business; thus young Marie-Anne, like Céline Guichavoi before her, had a role model for female entrepreneurship. When Marie-Anne moved to Pont-l’Abbé as the bride of Louis Le Minor, she found a town with a thriving tradition of clothing, and especially of embroidery. Bigouden costumes have long been renowned for their thickly embroidered patterns of spirals, chains, fishbones and sunbursts, and for their starkly beautiful color patterns of orange and gold on black. Embroiderers, both men and women, were highly-respected artisans in the community. By the early twentieth century, dozens of embroidery workshops offered their wares to locals and visitors alike. The Pichavant family had collected many of these workshops into a giant factory employing hundreds of embroiderers. Coming from a family that specialized in clothing, Marie-Anne was naturally fascinated by all this.

Bigouden embroidery

When the Depression struck in 1929, the Le Minor family was not as badly affected as most, since the milling business could depend upon a fairly inelastic demand. But times were tough for the embroidery business. Collapsing demand drove many embroidery workshops, including the large Pichavant factory, out of business, and hundreds of workers lost their jobs. Worst affected were young women, who could find no other work; many of them began to drift off to larger cities, supporting themselves in ways that were not always seen as honorable. Marie-Anne Le Minor was horrified by this, and had the resources to do something about it.

One of the embroidery-based cottage industries of Pont-l’Abbé was the fabrication of dolls’ clothing, especially those featuring the striking Bigouden design motifs. Marie-Anne hired some girls to continue with this tradition, unconcerned at first as to whether she could actually sell the dolls they produced. She then taught them how to clothe dolls in the borledenn style of her own Porzay region. From this grew a new idea: dolls costumed in each of the local traditions of Brittany, then of France, and later all over Europe. Business was slow at first, but Marie-Anne was a persistent and eminently sociable person, and the reputation of her dolls (and also of her exasperatingly demanding quality control) soon spread.

The breakthrough came in 1937, when Marie-Anne presented her dolls at the world’s fair in Paris. Success was instantaneous; within weeks her workshop was receiving orders from all over the world. She hired dozens more embroiderers, male and female, and eventually had to shift them into a warehouse across the quay from her husband’s mills. She began moving in rarified Parisian social circles, becoming close friends with the likes of the hotelier Charles Ritz and the writer Colette.

A Le Minor doll clothed in the Bigouden style; embroidery detail.

World War II brought a sudden if temporary end to the availability of celluloid, from which the dolls’ bodies were made, so Marie-Anne diversified her business into human clothing, as well as other embroidered goods such as tablecloths, tapestries and church banners. But World War II had a greater impact on the Le Minor family than just the shortage of celluloid.

*

To call the Second World War a traumatic time for France would be a serious understatement. For a nation whose salient national characteristic is pride, the war was a humiliating take-down: the sudden and ignoble collapse of the French army in 1940, followed by four years of German occupation and then a devastating American-led counterattack in which the French played only a minor role. The French Resistance fighters provided the only glimmer of glory during this sombre period, such that it is still considered poor form to point out that the Resistance really only took shape during the final year of the Occupation.

From the viewpoint of Brittany, with its conflicted, half-hearted sense of French identity, the war period exacerbated social tensions that had plagued Breton society since the French Revolution. Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, all of French society showed a schism between the traditional and the modern: Catholic, well-established, often royalist or aristocratic conservatives confronted secular, republican, often proletarian liberals. In Brittany a further division added a linguistic, cultural spice to the confrontation: The traditionalists were often Breton-speaking and imbued with Brittany’s Celtic culture, whereas the progressives and socialists usually adopted French as their language and their identity.

The linguistic divide was not actually as clear-cut as both sides might have wished; there were Breton speakers in the French Communist Party, for example, and many of the oldest aristocratic families in Brittany had spoken French for generations. Nonetheless, a pattern emerged whereby a Breton linguistic or cultural identity became associated with political conservatism and a deep Catholic faith. As one instance, the Breton language was taught in Catholic schools, while its use by secular school pupils was a punishable offense. The most influential Breton cultural organization in the early twentieth century, Bleun-Brug, was founded by an abbot, Yann Vari Perrot, and took as its motto, “Breton and Faith are brother and sister in Brittany”.

The period between the two world wars witnessed the growth of nationalist sentiment in all of the Celtic lands (especially Ireland). In Brittany, the project of political autonomy appealed to the sense of repressed identity that had simmered since the time of the Duchess Anne. The arrival of the conquering Germans in 1940 brought that fire out into the open.

Most of the Breton nationalists, of course, wanted nothing to do with the Germans, any more than they did with the French. Some, however, saw the collapse of the French Third Republic as an opportunity too good to miss. Olier Mordrel and François Debeauvais, leaders of the outlawed Breton Nationalist Party, traveled to Germany to try to persuade the Nazis to separate Brittany from the rest of France. (The Germans were not interested.) Célestin Laîné, who had been trying to organize an armed Breton guerrilla group along the lines of the Irish Republican Army, ended up offering his brigade’s services to the Wehrmacht and fighting against the Resistance. Although most Bretons, on both sides of the political divide, found such pro-German antics to be deplorable, the progressive forces were not above using them to paint all of their Breton-speaking adversaries as Nazi collaborators.

When Charles de Gaulle and the Resistance swept into power in the exhaust fumes of Patton’s tanks, they instigated a thorough and sometimes vindictive purge of those suspected of collaboration with the Nazis and their puppet Vichy government. In Brittany, the purge took on the aspect of a crusade against the Breton language and supporters of Breton culture and traditions. Having worked hard to preserve the Bigouden tradition of embroidery, Marie-Anne Le Minor found herself in a curious position in the face of the post-war purge.

*

One of the victims of the post-war purge was Marie-Anne’s brother, Dr Jean Cornic, who spent three weeks in a freezing prison cell in late 1944 — ostensibly for having cared for German soldiers during the Occupation, but in fact because he had been the president of Bleun-Brug back in the 1920s. (Others fared much worse. In December 1943, one of the first high-profile assassinations committed by the Resistance in Brittany was that of the elderly abbot Yann Vari Perrot, who had been Bleun-Brug’s founder 38 years earlier.)

Like most Bigouden families, the Le Minor clan had their political divisions: while René went into local politics on the progressive side, his nephew Jean was a strong supporter of Bleun-Brug (along with Dr Jean Cornic, his maternal uncle). When the post-war purge of “collaborators” began, the Le Minors found it wise to compensate for the Breton orientation of their clothing business by emphasizing their Frenchness in other areas. For this reason, none of the children born in the decades following the war were raised in the Breton language.

The Le Minor doll workshop in about 1950 (drawing by Mathurin Méheut).

By the 1950s, Marie-Anne’s sons Jean (1923-2014) and Jacques (1927-2013), who had expected to continue with the family’s milling business, found themselves involved instead with their mother’s clothing factory as demand for the mills’ products wound down. The mills on the bridge finally closed in 1958, after at least eight centuries of operation. The mills themselves were dismantled and converted into homes (including one for the now-widowed Marie-Anne), and a storefront for Marie-Anne’s dolls and clothes. Today, the bridge of Pont-l’Abbé is still one of only three inhabited bridges in France.

Although the baron’s mills were now history, the prominence of the Le Minor family continued through Marie-Anne’s clothing business. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Marie-Anne cultivated close friendships with Breton and other artists, such as the expressionist painter Mathurin Méheut, the stylist Dominique Villard, the jeweler Pierre Toulhoat, and the weavers from the Aubusson tapestry workshops, especially Dom Robert and Jean Picart Le Doux. Each of these contributed designs that were used on Le Minor tablecloths, clothing, drapes, church banners, and decorative panels.

La Sirène (designed by Pierre Toulhoat, embroidered by Cécile Le Roy).

The prosperity of the Le Minor clothing business reached its peak during the 1970s with the worldwide fad for the kabig. Originally a tightly-woven hooded woolen cloak worn by Breton fishermen and kelp gatherers against the cold salt spray of the North Atlantic,  the Le Minor factory transformed the kabig into a fashionable all-weather overcoat that enjoyed the same success as Marie-Anne’s dolls had forty years earlier. By 1977 the factory was the largest employer in the Bigouden region, with 450 seamstresses on its payroll. Within three years, however, there were none.

the Le Minor factory transformed the kabig into a fashionable all-weather overcoat that enjoyed the same success as Marie-Anne’s dolls had forty years earlier. By 1977 the factory was the largest employer in the Bigouden region, with 450 seamstresses on its payroll. Within three years, however, there were none.

*

Many factors conspired to bring Marie-Anne Le Minor’s empire down. The main one was the fickleness of fashion: By 1980, tastes in clothing had moved towards a more urban, punky look, and the folky fashion of the kabig was left in the dust of a new decade. Then there was the general global financial situation, known at the time as “stagflation”, one of whose problems was that banks would not lend money to businesses in need of rapid adaptation. There was also a growing trend to shift labor-intensive industries such as clothing out of First World countries and into cheaper regions like Asia, Latin America, and Africa. The Le Minor clothing business, with its commitment to local Breton folk art, was not disposed to take advantage of this trend, and suffered great competitive pressures as a result.

Finally, there was the social and political situation of the day. The labor unions representing the hundreds of Le Minor workers were, of course, upset at the threat to their employment; and like all French unions, they tended to regard the problem in stark class-struggle terms. The Le Minor family, the last of the mill barons, with their nice houses, their ample bank accounts and their well-educated children, were not going to suffer as much as a seamstress who lost her job and had nowhere else to turn — the French textile industry was in decline everywhere. This situation, combined with the ingrained French suspicion of wealth and the history of cultural conflict between “traditional” Brittany and “modern” France, poisoned the atmosphere in the town of Pont-l’Abbé.

A series of layoffs in 1977 and 1978 provoked a strike in which members of affiliated unions from all over western Brittany came to reinforce the picket line in front of the Le Minor factory. At one point the factory manager, Jacques Le Minor (Marie-Anne’s son), was held prisoner in his office for two days, and his home was ransacked. Personal friendships of several decades were shattered overnight; and the banks, already reluctant to extend further credits to the Le Minor business, now treated it as a sinking ship and left it to its fate.

In March 1980, a defeated Jacques Le Minor signed the bankruptcy papers that put an end to his mother’s manufacturing business. The Le Minor clothing marque was acquired by a competitor, who had the clothes made elsewhere. All that was left of the family empire was the Le Minor storefront on the bridge, run by Jacques’ older brother Jean — himself approaching retirement age — which now sold only Breton cultural items made by others.

*

There was one bright spot during this gray period: Brittany’s Celtic culture was finally losing its pariah status in the eyes of the rest of France. The change began with music. The folk-revival movement that began in Great Britain came late to France, but when it arrived, Brittany caught it first. Young musicians like Alan Stivell and older ones such as Yann Fanch Kemener suddenly found themselves in demand; for the first time in decades, young players took up traditional Breton instruments (the Celtic harp, the bombarde, the biniou) and brought new life to tired Celtic festivals. Not content simply to copy traditional styles, the new generation began to experiment with their musical heritage, adding elements from rock, jazz, and classical music. Slowly, the Breton identity became a source of pride for all social classes, not just the diehards of the ancien régime.

When Gildas Le Minor (son of Jacques) took over the storefront after his uncle’s retirement in 1987, he was able to tap into this new cultural current. Tablecloths printed and embroidered with Bigouden motifs graced the tables of the finest restaurants in Brittany and elsewhere; designer scarves marked a partial return to the world of fashion; embroidered panels and church banners provided employment for a small number of embroiderers, protecting, for a time at least, this ancient Pont-l’Abbé craft from extinction.

La Mer tablecloth (designed by Mathurin Méheut).

Today the Le Minor family has spread all over the world, from Quimper to New Zealand, but in the generations after Gildas Le Minor, not a single one of the descendants of René Louis Le Minor and Céline Augustine Guichavoi lives in the Bigouden area. This tree spreads by windblown seeds and not by roots. Yet every little girl who has loved a Le Minor doll, every pedestrian wearing an indefatigable kabig, every dinner plate set upon a colorful Bigouden tablecloth, testifies to the heritage of the soldier who returned from the Crimean War with gold in his pocket and a dream in his heart.

Pont-l’Abbé, September 2017

The bridge and castle of Pont-l’Abbé today (seen from upriver).

Sources and notes:

Quotes about Bigouden origins: A. Mahé de la Bourdonnais, Voyage en Basse-Bretagne chez les «Bigouden» de Pont-l’Abbé après vingt ans de voyages dans l’Inde et l’Indo-Chine (Paris: Henri Jouve, 1892), pages 9, 14, and 15; René Le Feunteun, De l'Hygiène des Populations maritimes de la Bretagne armoricaine, thesis for the degree of Doctor of Medicine, Faculté de Médecine et de Pharmacie, Bordeaux, 1899 (cited in “Les Bigoudens vus par les autres”, Cap Caval (Pont-l’Abbé, France) issue 10 (May 1988), pages 37–41). For the definitive genetic study, see Pierre Youinou et al., “Plasma protein polymorphisms in a puzzling Breton community, the Bigoudens”, Acta Anthropogenetica 7(3) (1983), pages 233–239.

On the word Bigouden: Not all sources agree on the etymology presented here; see C. Laurent, “L’origine du mot «Bigoudenn»”, Les Cahiers de l’Iroise (Brest, France), January–March 1973, pages 1–27; also a letter to the editor from R. Gargadennec in the subsequent issue (Les Cahiers de l’Iroise, April–June 1973, pages 141–142). Nonetheless it is common in Brittany, even today, to describe its regions in terms of the traditional costumes or headdresses once worn there. Thus the region around Quimper is known as the pays glazik on account of the blue tunics of its inhabitants, glaz being the Breton word for blue; likewise the people around the fishing town of Douarnenez are called penn sardinn — “sardine heads” — not, mercifully, for the shape of the headdress, but for the fact that the distinctive lacy hat was worn by women workers in the sardine canning factories. In the pays bigouden, the three-pointed headdress visible in early nineteenth-century drawings had disappeared by the end of that century, as the points merged into a cylindrical shape that grew ever higher as the decades passed. Nonetheless the name bigouden remained as the region’s moniker.

1848 |

1903 |

1928 |

1955 |

Traditional costumes were worn in the Bigouden area for far longer than in most parts of modern Europe. Jakez Cornou kept a sort of census of bigoudènes (women who wore the Bigouden headdress on a daily basis). There were 3,567 of them in 1977, 643 in 1992, and 14 in 2003. The last of the bigoudènes, Maria Le Berre (nicknamed Maria Lambour), passed away on 20 October 2014 at the age of 103.

Maria Lambour on her 100th birthday in 2011.

(Photo: Le Télégramme)

See Simone Morand, Histoire du costume glazig et bigouden (Châteaugiron, France: Yves Salmon, 1983); Jakez Cornou, La Coiffe Bigoudène: Histoire d'une étrange parure (Pont-l’Abbé, France: Editions SKED, 1993); and the following articles in Le Télégramme (Brest, France): “Mariannick”, 18 October 2003; “Trigoudènes”, 8 December 2003; “Maria Lambour n’est plus”, 21 October 2014.

The only Bigouden town: In 1860 Pont-l’Abbé was indeed the only town of any importance in the Bigouden area, but this had not always been the case. From the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, Penmarc’h, at the southwestern corner of the Bigouden peninsula, was a prosperous fishing town whose population, at its peak, might have exceeded ten thousand. Penmarc’h fell into a sharp decline after 1550 as the cod banks on which its economy depended became depleted; in the 1590s the town was largely destroyed during the League Wars, from which it never really recovered. The name Penmarc’h, which means “horse’s head”, is a Breton translation of the Latin Cap Caval — the name by which the Romans called the Bigouden area, on account of the shape of the peninsula on which Penmarc’h sits. See François Quiniou, Penmarc’h: son histoire, ses monuments (Autremencourt, France: Le Livre d’histoire, 2010; reprint of 1925 original); and Rémy Monfort, Penmarc’h à travers ses historiens (published by author, 1985).

On the nameless river: Indeed it appears that if the river that runs through Pont-l’Abbé ever had a name of its own, it has been lost to history. In all written records and oral traditions it has been known only as la rivière de Pont-l’Abbé (or ster ar Pont-an-Abad in Breton). The only exception seems to have been Breton sailors who called it an Teir or an Theyr; but even this name, which translates as “the Three”, is more descriptive than nominative, referring to the fact that the river splits into three streams at its delta. See Olivier Garros, Jacques Godin, and Serge Duigou, La Rivière sans nom (Lesconil, France: Editions Les îles du désert, 2008), pages 16-17.

On the castle: The château des Barons du Pont was erected in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but has been partially destroyed and rebuilt three times since. Today it presents what Serge Duigou refers to as an “architectural jigsaw puzzle”. Of the four original corner towers, only the northeast one remains. See Gérard Le Moigne, “Le Château de Pont-l’Abbé”, in Bulletin de la Société Archéologique du Finistère, volume CXXXI (2002), pages 185-215; also Paul du Chatellier and Emile Ducrest de Villeneuve, Pont-l’Abbé-Lambour, Fouesnant et Plogastel-Saint-Germain, part of the series Paysages et Monuments de la Bretagne (Paris: Société des Librairies-Imprimeries réunis, 1893), pages 18-32.

Hyacinthe Le Bleis: Serge Duigou, “Pont-l’Abbé, capitale du pays bigouden”, in Le Pays bigouden à la croisée des chemins, acts of a colloquium held in Pont-l’Abbé, 19-21 November 1992, organized by the Université de Bretagne Occidentale and the magazine Cap Caval (Bannalec, France: Imprimerie Régionale, 1993), page 37. See also Serge Duigou and Annick Fleitour, Pont-l’Abbé au coeur du Pays bigouden (Quimper, France: Editions Palantine, 2009), page 33.

Penn-ar-Pont: The half of Pont-l’Abbé that lies north of the bridge, known as Lambour, was long the working-class district of the town. Penn-ar-Pont (“bridgehead”), the neighborhood of Lambour immediately adjoining the bridge, was centered around a small church known as the Chapelle Saint-Sauveur (or Chapelle du Christ, so called after the name of the bridge). This chapel served as the venue for several angry meetings of the Lambour proletariat during the early days of the French Revolution, but this did not save it from the general fate of religious buildings during that turbulent period. Confiscated by the state in 1796, Saint-Sauveur and its adjoining presbytery were sold to Jean-Baptiste Lamy, and then in 1804 to a non-Breton family named Viers. Bernard Viers dismantled the chapel and sold off its stones, using many of them to build a handsome home for himself on the rue Meur (today called rue Victor-Hugo), the main street of Lambour leading from the bridge. With this house began the gentrification of Penn-ar-Pont. A family named Février acquired both the house and the ruined chapel in the early 20th century; the Le Minor family bought it all from them in 1949. By this time a substantial fraction of Penn-ar-Pont was in the hands of the eleven children of René Michel Le Minor. See Serge Duigou, Lambour en Pont-l’Abbé (Quimper: Editions Ressac, 1987), pages 9-14.

Last of the stones from the Saint-Sauveur chapel.

Trains: By 1912, Pont-l’Abbé was the junction point for three train lines: the main one from Quimper; the tren birinik (“barnacle train”) that served the Bigouden fishing ports as far as Saint-Guénolé; and the tren karotez (“carrot train”) from Audierne that brought agricultural produce from the Bigouden farms west and north of Pont-l’Abbé. These last two narrow-gauge railways, built at the same time as the Trans-Siberian Railway in Russia, acquired the affectionately derisive nickname of Transbigouden. Passenger service to Pont-l’Abbé ended in 1946, and the last freight train left Bigouden soil in 1988. See the following works by Serge Duigou: 1884: Un train pour les Bigoudens (Quimper, France: Editions Ressac, 1986); Quand nous prenions le train birinik (Quimper, France: Editions Ressac, 1983); Quand s’essouflait le train carottes (Quimper, France: Editions Ressac, 1984).

Pont-l’Abbé railway station in 1910.

Riou family: Serge Duigou, L’Ile au trésor (supplement to La Rivière sans nom, op. cit.; Lesconil, France: Editions Les îles du désert, 2008), pages 4-8. The “treasure island” of the title is the Ile Chevalier, the largest of the estuary islands downstream from Pont-l’Abbé, whose rich soil and easily defended situation were long the property of the Baron du Pont. When the last baron was chased off during the French Revolution, the Riou family wound up owning the bulk of the Ile Chevalier, indicating that they were already wealthy under the ancien régime; but not being aristocrats, their wealth was not subject to confiscation by the new Republic. Curiously, one of the demands of the Red Bonnets in 1675 had been the relaxation of the clerical ban on lending money at interest. One could speculate that the Riou financial operations might have been influential even back then.

The mills on the bridge: Jacques Le Minor, “Les Grands Moulins de Pont-l’Abbé” (masters thesis for the Ecole Supérieure des Sciences Economiques et Commerciales (ESSEC), Paris, 1947). The baron’s own mill contained two sets of millstones: a meilh ruz (red mill) for animal feed, and a meilh gwinn (white mill) for human-destined flour. The smaller mill run by Notre Dame des Carmes had only one white-mill stone. By the time of the French Revolution, the buildings housing these mills were in poor shape, although the mills themselves were still functioning. Seized by the Republic after the last baron fled into exile, the two mills were sold separately at public auction. On 19 July 1794 (1 Thermidor AR 2), Jean Le Pape acquired the baron’s mill for 8,275 pounds. (Le Pape also acquired a mill seized from the large property of the de Cheffontaines family of Clohars-Fouésnant.) The smaller mill, nationalized from the now-banned monastery, went to Claude Vacherot of Quimper on 13 May 1798 (24 Floréal AR 6) for 44,000 francs. Two years later, Jean Le Pape acquired the smaller mill too. He sold both mills in 1804, but bought them back in 1833. In 1848 they passed to his son René Le Pape, who quickly sold them off to Hyacinthe Le Bleis.

In 1859, Le Bleis transferred ownership of the vastly-expanded mills to a company called Duval-Tranquardière, as part of a sweeping business deal; but the deal went sour, and Le Bleis went to court to recover the mills, which he succeeded in doing in 1867. Le Bleis died in 1869, and the following year his widow sold the mills and the warehouse to Félix Laurent, who owned them until the 1906 fire; he then sold them to René Michel Le Minor.

Le Minor embroidery business: The official history of the Le Minor embroidery and clothing business is found in Armel Morgant, Le Minor (Spézet, France: Coop Breizh, 2012). Specifically on the dolls, see Anne Libouban, Les Poupées Le Minor: Un petit monde de haute couture (Spézet, France: Coop Breizh, 2011). See also Françoise Boiteux-Colin and Françoise Le Bris-Aubé, Le Monde des Bigoudènes (Brest, France: Le Télégramme-Editions, 1999), pages 16-22.

Breton cultural identity: The conflict between Brittany’s regional identity and Parisian centralism took its most violent form in the revolt of the Chouans (1792-1800), Breton traditionalists who resisted the secular and rationalist ideals of the French Revolution. The revolt and its bloody suppression convinced many republicans throughout the nineteenth century that the Breton identity had to be stamped out, and they took this conviction to sometimes ludicrous extremes. In 1859, for example, the emperor Napoléon III ordered the dissolution of the Archaeological Society of Finistère because its focus on Breton history made it “politically suspect”. See Yves Coativy, Paul de Chatellier, Collectionneur Finistérien (Brest, France: Université de Bretagne-Ouest, 2006), chapter on Armand du Chatellier (1797-1855). The problems of Breton identity in the twentieth century, including the growth and persecution of Bleun-Brug, are treated in Yann Fouéré, La patrie interdite (Paris: Editions France-Empire, 1987).

Cornic family and the post-war purges: Interview with Jean Cornic (son of Dr Jean Cornic), Rennes, 19 May 2015. Dr Jean Cornic was sprung from prison by Xavier Trellu, a Resistance leader who knew that Dr Cornic had also clandestinely treated Resistance fighters. See Arthur Plaza, From Christian Militants to Republican Renovators: The Third Ralliement of Catholics in Postwar France, 1944-1965 (New York University PhD dissertation, September 2008), page 233. For a general discussion of this unpleasant period in French history, see Peter Novick, The Resistance versus Vichy: The Purge of Collaborators in Liberated France (London: Chatto & Windus, 1968). For a specifically Breton viewpoint, see Yann Fouéré, La patrie interdite (Paris: Editions France-Empire, 1987), especially Part 6, “Les moissons piétinées” (“The trampled harvest”); Fouéré mentions Dr Jean Cornic on pages 78 and 379. It is telling that no objective treatment of the post-war purges has been published in the French language. It is still a touchy subject, even after seven decades.